Selected Newsletter Articles

"The SVCC News" is the newsletter of the Sacramento Valley Citroën Club. Six issues are published per year. Re-publication on a single use basis is permitted if full credit and source of article is listed.

If you have an original article that you would like to submit for publication in our newsletter, please submit it to: svcc@designmassif.com

Do you want to translate this page into another language? Try these links:

Systran

or

BableFish

appeared in issue #175, page 2

The Fathers of the 2CVWritten by Fabien Sabates

The 2CV is, above all, a work of tenacity.

The 2CV is Pierre Boulanger, someone we can no longer ignore today.

But who is Boulanger?

Pierre Jules Auguste Vital Boulanger was born in Sin-le-Noble, in the north, March 10, 1885. Shortly afterward, his family immigrated toward the capitol to try to make a living. The young Pierre had to interrupt his studies at Chaptal secondary school to get a job. From 1906-1908 he did his military service in the 25th Batallion in Satory. It was here that he met and became friends with Marcel Michelin. In 1908, at 23 years old, Pierre decided to leave his country. He left with several friends for the United States. First, he worked on a ranch, then at the Seattle Electric Company. Two years later, he became a draftsman at the office of Dudley, an architect in Seattle. He progressed rapidly in the practical knowledge of buildings and, in August, 1911, founded a construction company in Victoria, Canada under the raison socaile of "Modem Houses Ltd.", and took presidency of the business.

The declaration of war in Europe on August 2, 1914 caught him unawares an his rise to the top. Even so, out of pure patriotism he didnít hesitate to leave a comfortable and secure life to return to France. September 3, 1914, he rejoined his army corps as a corporal. Posted to a squadron of formation planes in November of 1914, he was given tenure as observer of the first order in January of 1915. (??)

During the war he would pay as much with his person and good will, as with his perfect conscience in the execution of his mission, so much so that he was always given the difficult mission, "the missions of confidence", said his superiors.

In his squadron, the "MF36", he specialized in taking aerial photographs on reconnaissance missions. Boulanger also invented the installation of a camera on board the plane, the same previously used by the "aerostiers", and with this camera he carried out almost all photo taking on a large scale in his sector. These negatives, of which the oldest go back to March, 1915, would permit the establishment of the first guiding maps of the Nieuport sector and the first leading map of the Belgian army.

Boulanger would actively take equal part in aerial combats, the earliest of which Iíve found to probably have taken place on July 31, 1915, but he participated in many bombardments both day and night.

In the air he would be machine gunned three times by the enemy and his cameras were put out of commission, but, for the number of times he flew, his plane received only light attacks. It was Joffre, the conqueror of the Marne, who would award to him in person the military medal, the 14th of June, 1915; on this occasion, the general of the North and N-E armies wrote to him: "Giving the squadron the best example of courage and drive, and even further, wounded, undertaking assurances that at all costs the orders would be executed and continued until the mission was fulfilled." Boulanger obtained the "Cross of War" that same year.

October 31, 1916, Ferdinand Foch, the future Marshall of France - thus still assistant to Joffre - cited to Boulangerís headquarters on the order of the army as "a pilot of courage and remarkable energy..."

Patented military pilot, he logged over 300 hours of flight time by the Autumn of 1916. Nevertheless, flying, it seemed to him, was not his strength. In 1917, his plane would overturn, and he would escape with six months in the hospital for a crack in his spinal chord.

The consecration of these military states was the "Journal Officiel", that announced him on January 7, 1917 for receiving the Legion of Honor, emphasizing his two wounds and two citations. Certainly a merited reward, but it would not be the last, for one must add various foreign decorations and pas des moindres. May 30, 1917, a note of service from headquarters saw Pierre Boulanger named commander of the photography section of the French army by the General Commander in Chief. Later in the year, even though he was already occupied with important functions as secretary for the inter allied community of aviation, he was transferred to assist Secretary of State of Aeronautics as head of the French-American section. (This signifies that he was responsible for the Wason with the American army.) It must be said that his perfect knowledge of the English language was a great advantage, but it was, above all, his "loyalty, devotion, precision, and clarity in thinking, his tireless and intelligent activity" that made him the choice out of many others. November 11th remains an important date in the history of Pierre Boulanger. It sounded the liberty of the world, but 32 years later it would take his life. His accidental death, besides the grief and sadness it caused his family, friends, and his close collaborators, would also disrupt every project at the factory; one of the directors, under his orders, exclaimed: "Pierre Boulanger is more than ever the biggest of all the problems he ever put in front of us."

But weíre not there yet.

Boulanger had a great masterpiece to accomplish.

SOURCE: CitroŽn 2CV Album © 1992 by Sabates. Translation from French by Dene & Alicia Barrett

appeared in issue #175, page 3-4

French RevelationWritten by Tony Dron

A car for the people, a kind of Traction Avant from the Bauhaus School, an idea which is still changing the world: Tony Dron on the umbrella on wheels

The French should love the CitroŽn 2CV more: after all, it changed their world, finally bringing rural France out of the horse and cart age. From October 7, 1948 when the 2CV was unveiled at the Paris Show, millions of peasant farmers could afford their first car.

Most joined a long waiting list for this remarkable small car, designed to carry four people and 50kg of potatoes; reliable and cheap to run, it could go flat out all day at 40mph and return more than 50mpg.

Certainly, we Brits have taken it to our hearts but it took some decades for us to appreciate its true place as a modest but truly great car. Today, the most unexpected people keep a 2CV here and you can't drive through London without noticing dozens of them. Over in Paris, when Ari Vatanen was due to drive a works CitroŽn in the Paris-Dakar he turned up at the pre-rally press conference in his private 2CV, astonishing everybody, including the CitroŽn people.

It's sad that the 2CV is disappearing fast from French roads: late in 1996, in Paris with one of the very earliest 2CVs (1951)∑I did a little survey while Rich Newton took his photographs with the Eiffel Tower in the background. After half-an-hour observing the roundabout above the Trocadťro Gardens, the score was Minis 12, 2CVs nil. Many of the locals, touched peut-Ítre by a Napoleonic lust for grand gestures and style, would like to pretend that it never existed, that there never was a need to mobilize a nation of hard-up peasants in a car a bit like an umbrella on wheels.

Misplaced Gallic pride aside, the thinking behind the 2CV is still changing the world. Its design philosophy, avoiding unnecessarily wasted energy is modern: add the desire to appear 'green'. and even the driving pleasure to be derived from the quick responses of a light car, and it's obvious that these ideas are growing, even fashionable, today.

The need for the original 2CV was established as long ago as 1935. following a classic piece of market research secretly carried out by CitroŽn throughout France. A year earlier the incredible Andrť CitroŽn almost broke the company to launch the advanced Traction Avant; forced to sell out to Michelin, CitroŽn himself faded away, a broken man but the result was that sound. Michelin modern management was brought to an enterprise bursting with creative ability.

The new Managing Director, Pierre-Jules Boulanger was a Michelin man to the core of his intellect (if not in his looks!), and his (possibly Michelin-inspired) dream of motorizing the peasant farmers was pushed towards reality. But that wasn't all, for the designers had a secondary agenda of sophisticated minimalism up their sleeves.

The team Boulanger assembled was formidable: Monsieur Brogly, chief of the Design Office; Andrť LefŤbre, creator of the Traction Avant; engineers Roger Prud' homme and Alphonse Forceau, the latter a gearbox specialist; and stylists Flaminio Bertoni and Jean Muraret. They set about answering Boulanger's requirements with astonishing ingenuity. The fascinating and significant point is that, at the start, the 2CV was more a designers' tour de force than a cheap car for the masses. The Bauhaus philosophy of form following function was pursued as a fetish in the prototypes, of which a series was built. This exquisite combination of the designer's art, the technicianís craft and the most exotic lightweight magnesium alloy chassis materials offered an original answer to the question of what a light passenger car should be. It was party a design statement to impress other designers.

The attitude behind it now seems more 21st century than pre-Second World War yet, with the specification apparently settled, CitroŽn had built 250 pre-production cars by May 1939.∑ It was expensive to make but the company was on the brink of launching the Toute Petite Voiture; the 2CV.

Then the war intervened and all the prototypes were said to have been destroyed except one which was dismantled and hidden in the lofts at CitroŽn Fertť Vidame test track, 130km west of Paris. In fact, loyal employees saved a handful and, incredibly, two more emerged from the lofts only last year. During the war, CitroŽn had much needed time to think again. To save money, the chassis was redesigned in steel. The essential technical elegance of the overall design was retained but it was ruthlessly simplified.

After the war, with the need for a dirt cheap practical car more pressing than ever, the 2CV design was further re-engineered for the age of austerity, making it disgustingly cheap to some, but that was the whole idea and its enemies were soon converted when they drove it. The ride on rough roads was amazing. It could go almost anywhere, it was reliable and it could lope along those long. tree-lined, straight Routes Nationales flat out all day, oblivious to the appalling gutter undulations which were not repaired for decades.

Even if the more snobbish elements of French society at the Paris Salon in 1948 considered the 2CV humiliatingly stark, almost a national disgrace, other designers appreciated its finer points and, rather more important, the rural community flocked to get it. The production men had got the price right and 2CVs joined the beret and Gauloises cigarettes as unofficial national symbols. The ingenious design was so practical that order books stayed full year after year.

Progressive increases in engine size also kept sales alive, through 425cc in 1965 to 602cc for the 2CV6 in 1970 (68mph; 0-60mph, 32.1sec; typically 40~50mpg); several attempts were made to supplant it but the original look just went on and on selling until its factory itself became a museum piece of outdated, labor-intensive manufacturing techniques. That Paris factory at Lavallois, built in 1883 and later adapted for 2CV production, closed in 1988.

Easy and comfortable to drive, these cars never lost their charm nor a sense of fun. Despite alarming angles of roll, road holding and handling are excellent, as is braking performance. The dashboard gear lever. thought awkward by some who have not used it, is brilliantly simple to operate. A good 2CV driver becomes an expert in the conservation of momentum, its theory and practice, and, whenever the run shines, the roof can be rolled back in seconds. Owners love these unique, versatile machines.

I refer to my own 1983 2CV as Ma poubelle de course because many still consider the 2CV a cheap, nasty little thing. They should take a closer look at its engine, built like a high quality high revving racing unit in miniature; those super light door handles, so clever and elegant; the suspension system; the inboard front brakes and every detail of design.

The inevitable conclusion is that the 2CV philosophy is still changing the world and, for sure, the best is yet to come from the the Toute Petite Voiture.

Source: Written by Tony Dron; © Classic Cars Magazine

appeared in issue #176, page 3

Reskinning my CamelWritten by Jack E. Davis

Animals like snakes, lizards and such are able to renew their skins periodically. This would have been a nice feature for the Mehari, which means Camel in French. Mehari's were made from a standard 2 CV frame, a skeletal metal frame work, which supports a plastic body. The Mehari's were touted as the car you couldn't care less about. The body was made of Cycolac ABS plastic, one of those man-made miracles that has the strength of metal, but none of its weaknesses. The claim was that you could leave it outdoors, year after year, and it wouldn't rust, peel or need painting. Well it wouldn't rust or peel, but what they didn't say was that it would erode, crack and fade. Another one of those miracle wonders that didn't quite live up to it's expectations.

I purchased a Mehari that had sat in the desert of Tucson, AZ for many years. The Arizona sun had not been kind to the Mehari. I decided to restore the Camel and removed all the plastic body panels, even removed the skeletal frame work: in short I stripped it down completely. If you try this you may run into the same problem I did. To remove the side panels you must remove the windshield and dash panel. Removing the windshield turned out to be a bear of a problem. The windshield is held to the skeletal frame by a nut on each side and are really difficult to get at. That is only part of the problem, dust and crude will have settled in the socket that the windshield slides into, which will make removing the windshield next to impossible. I had to take some drastic steps to remove mine.

I had seen examples where repairs to the plastic had been made using fiberglass and resin, didn't look too good to me. I found a plastic glue made by Devcon which they call Plastic Welder (S-220), that works well, not as good as I would like, but it works. In some areas I used a polyester reinforcing cloth with the glue. I believe that welding, e.g. using a system similar to that used to repair plastic radiators tanks, might give better results. In addition to the glue, I had to use aluminum plating at the floor board area. Here I used the aluminum on both sides and joined them with POP Rivets. This area was badly damaged and missing sections. If I had taken this section to Tucson, I think they could have built up this area with Rhino spray, more on this later.

I found the Cycolac in like new condition in areas where it had not been subject to the sun. In some exposed areas it seemed to have eroded and was only 1/4th or less, the thickness of the protected areas, like 1/64th. I was hoping to run across some kind of coating that would reinforce the panels and hold up to the weather. While in Tucson I came across an ad advertising spray on pickup bed liners, called Rhino Linings. I contacted the dealer and after looking at the product and results felt that it would do what I was looking for. On my next trip to Tucson I took the tail gate panel to try out. I was pleased with the results and had more panels done at a later date. The Rhino Lining is a spray-on polyurethane product. They offer a smooth or textured finish. I choose the smooth finish. You also get a selection of colors. For best results I would recommend removing all panels, a big job, and have them sprayed individually and not more than 1/16th to 1/32nd thick. If you are interested, call the company at (800) 447 1471 for the nearest dealer and if in the Tucson area call (520) 888-2480 or (800) 337-3058. This stuff can be used in a variety of applications.

I still need to have the two side panels sprayed, and when done, I'II be able to re-assemble the Mehari. When completed I'II send some pictures.

Publishers note: There is a company in France that specializes in reproducing NEW body panels for Mehariís as well as new canvas tops/side curtains, and even new seats! Visit their web-site http://www.mehari.com or send them e-mail mehari-club@enprovence.com or send them some snail mail to: SOCIETE MEHARI CLUB CASSIS

Quartier du Bregadan

13260 Cassis, FRANCE

As an additional side note, Sunscreen with a high SPF is very effective at protecting ABS from damaging UV rays.

appeared in issue #176, page 4

My Husbandís Love AffairWritten by by Beth Aaland

In the year 1966, I knew I had to take a backseat when my husband first saw and bought a second hand CitroŽn. No longer did the word citron define a class of tangy fruit to me; CitroŽn became my adversary for the rest of my married life. First I had to learn to pronounce it as the French do. Cit-ro-en, not cit-ron. I admit my Americanization of the name continues off and on. I still, on occasion, say citron when I think of the lemon-like qualities of the car (of course these are few and far between).

There is no question about the comfort, the smoothness of the ride and the flexibility of the car when riding over rough, uneven terrain. Beauty however is in the eye of the beholder. While some have said it is the funniest looking car they have ever seen, my husband thinks of it as beautiful. The "turtle" or "platypus" look is, to my husband, the most streamlined, aerodynamic, efficient body in the world. "Form follows function" is his philosophy in the realm of esthetics.

Since it was the only car we had at one time, I also learned to appreciate its superior qualities. I drove the stick shift with no trouble and enjoyed the feeling of distinction when I became aware of people waving and smiling and wondered if it was at me or at the car. At school, the students watched as I raised and lowered the body of the car with a push of a button. Like an elevator, they said. My husband has dedicated his life to the inward working of the engine, the hydraulic systems, and the electrical system. He has operated on the inside of the car, choosing to redesign it to his specifications and for his needs.

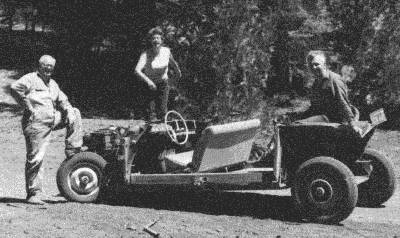

Caption: My husband is on the left, with me in the center

Once he created an open-air jeep by cutting off all sides and leaving only the frame which was designed to carry odd shapes, sizes and weights. It was affectionately called the "Mean Machine" by a group of 15 Boy Scouts who rode in it when they helped clear a hiking trail in the mountains.

If one was good, a dozen were better. Over the years, it became necessary to have spare parts and of course, by then everyone in the family had one. Also there had to be one for every conceivable purpose my husband could think of.

My green CitroŽn was very considerate. It never broke down when was on the road. It always waited until I was in the driveway before it would finally give in to some small problem which could only be fixed by my husband or one of my sons. The major problem for me occurred when the starter became independent of the push button on the dashboard. It happened that the engine stalled at red lights. Then I practiced a very precise routine especially when I was alone. I had to make sure the gear was in neutral, the key to the engine was on and the car door when open didn't hit the car along side waiting for the light to change. I dashed to the front of the car, pulled up the hood, held it up, while I edged along the side where the starter was located and pushed the small starter button until I heard the hum of the engine. Then took the time to lower the hood carefully (even though I had a chorus of horns behind me) so it wouldn't blow up in the next wind, dashed back to the drivers seat and accelerated the engine so I didn't have to repeat the procedure.

In spite of these occasional CitroŽn lapses, we rescued my husband once when he was pulling a 24 foot cabin-cruiser and had broken down on the freeway. My trusty CitroŽn and I were at home when he called, asking for someone to tow him back to Livermore. We ended up with my car pulling his car, a trailer and the cabin cruiser. On that Halloween night when we drove through the city of Pleasanton, we stopped the parade and entertained the people lined up on the side of the road with our ghoulish caravan.

The winter I commuted to San Francisco, I decided I needed an automatic transmission and an engine that didn't choose to stop at red lights, so with my husbands dubious approval, I bought a legless Colt which I continue to drive.

My husband however, continues his love affair with CitroŽns. He has passed on his great love to our three sons.

VIVA LES CITROňNS!

|